1989 Atlantic hurricane season

| Season summary map | |

| First storm formed | June 24, 1989 |

|---|---|

| Last storm dissipated | December 4, 1989 |

| Strongest storm | Hugo – 918 mbar (hPa) (27.12 inHg), 160 mph (260 km/h) |

| Total depressions | 15 |

| Total storms | 11 |

| Hurricanes | 7 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 147 |

| Total damage | $10.74 billion (1989 USD) |

| Atlantic hurricane seasons 1987, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991 |

|

| Related article | |

The 1989 Atlantic hurricane season was an active season that produced fifteen tropical cyclones, eleven named storms, seven hurricanes, and two major hurricanes. The season was officially designated from June 1, 1989, to November 30, 1989, dates which conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones develop in the Atlantic basin.[1][2] The season began with Tropical Storm Allison on June 24, and ended with Tropical Storm Karen, which dissipated on December 4.

The most notable storm of the season was Hurricane Hugo, which caused $10 billion (1989 USD, $17.7 billion 2012 USD) in damage and 111 fatalities as it ravaged the Lesser Antilles and South Carolina of the United States. Hugo ranked as the costliest Atlantic hurricane until Hurricane Andrew in the 1992 season, and has since fallen to the eighth costliest hurricane following the even more destructive storms during the 2000s decade. Few other storms in 1989 caused significant damage; Tropical Storm Allison, Hurricane Chantal, and Hurricane Jerry combined caused extensive damage in Texas; Hurricane Dean also caused light damage in Bermuda and the Canadian province of Newfoundland. Overall, the storms of the season collectively caused 147 fatalities and $10.74 billion (1989 USD, $19 billion 2012 USD) in damage.

Season summary

Pre-season forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

| CSU[1] | May 31 | 7 | 4 | Unknown |

| Record high activity | 28 | 15 | 8 | |

| Record low activity | 1 | 0 (tie) | 0 | |

| Actual activity | 11 | 7 | 2 | |

Forecasts of hurricane activity are issued before each hurricane season by noted hurricane experts such as Dr. William M. Gray and his associates at Colorado State University (CSU). A normal season as defined by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), has eleven named storms, of which six reach hurricane strength, and two major hurricanes.[3] On May 31, 1989, it was forecast by CSU that there would be seven named storms, four of which would intensify into a hurricane; there was no prediction of the number of major hurricanes (Category 3+ on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale).[1]

Season activity

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1, 1989.[1] It was an above average season in which 15 tropical depressions formed. Eleven depressions attained tropical storm status, and seven of these attained hurricane status. Two hurricanes further intensified into major hurricanes. The season was above average most likely because of relatively small amounts of dust within the Saharan Air Layer. Four hurricanes and one tropical storm made landfall during the season [4] and caused 147 deaths and $10.74 billion in damage (1989 USD; $19 billion 2012 USD).[4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12] The last storm of the season, Tropical Storm Karen, dissipated on December 4,[4] four days after the official end of the season on November 30.[13]

Tropical cyclogenesis in the 1989 Atlantic hurricane season began with a tropical depression developing on June 16. Later that month, another tropical depression developed, and intensified, eventually becoming Tropical Storm Allison. After June, the month of July was slightly more active with three tropical depressions developing; however, the latter two (Hurricane Chantal and Hurricane Dean) did not form until extremely late in the month. August was the most active month of the season, with a total of seven tropical cyclones either existing or developing in that period.[4] Although September is the climatological peak of hurricane season,[13] only two tropical cyclones developed in that month, and both of which later become Hurricane Hugo and Tropical Storm Iris. Two tropical cyclones also developed in October, and the latter one in that month eventually became Hurricane Jerry. Finally, one tropical cyclone developed in November; it eventually became Tropical Storm Karen, and lasted outside the bounds of hurricane season, dissipating on December 4.[4][13]

The season's activity was reflected with a cumulative accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 135,[14] which is classified as "above normal".[3] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. ACE is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 34 knots (39 mph, 63 km/h) or tropical storm strength. Subtropical cyclones are excluded from the total.[15]

Storms

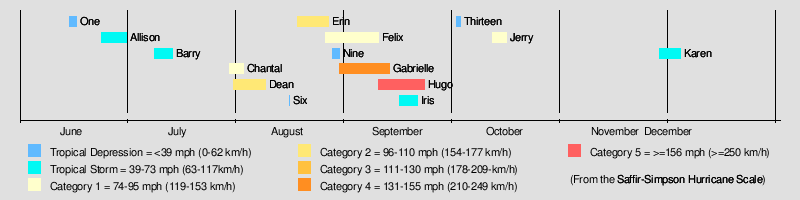

Timeline of tropical activity in the 1989 Atlantic hurricane season

Tropical Depression One

| Tropical depression (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | June 15 – June 17 | ||

| Intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min), Unknown | ||

The first tropical depression of the season developed on June 15 from a frontal zone [16] situated 440 mi (710 km) east of Tampico, Mexico.[17] The depression headed southeastward toward Mexico, and did not intensify into a tropical storm as predicted.[18] Nearing the coast of Mexico, the tropical depression was absorbed into a larger extratropical system on June 17. Although the tropical depression was in close proximity to land, there was no effects on land, and as such, there was no damage or fatalities reported.[16]

Tropical Storm Allison

| Tropical storm (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | June 24 – June 28 | ||

| Intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min), 999 mbar (hPa) | ||

The second tropical depression developed on June 24 in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico, from the interaction of a tropical wave and the remnants of eastern Pacific Hurricane Cosme. Heading northward, the tropical depression slowly intensified, becoming Tropical Storm Allison two days later.[19] Allison continued to slowly intensify, and made landfall near Freeport with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) on the following day.[20] While just inland, the storm dropped heavy rains, especially in Louisiana and Texas, where rainfall from Allison had peaked at 25.67 in (652 mm) in Winnfield, Louisiana.[21] Continuing over Texas, Allison rapidly weakened over eastern Texas, and transitioned into an extratropical storm on June 28. Although it rapidly became extratropical over land, the remnants of Allison wandered over the southern United States, but reached as far north as Indiana before turning south again and finally dissipating over Arkansas on July 7.[20]

Allison caused significant flooding in several states, especially Louisiana and Texas, where rain fell at over 20 in (508 mm) in some areas.[21] Furthermore, Allison produced 13.9 in (353 mm) of rain in Arkansas, which made it the wettest tropical cyclone recorded in that state.[22] Eleven deaths by drowning were attributed to the rains associated with Allison, and flood damage in Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi was estimated at $560 million (1989 USD, $992 million 2012 USD).[5]

Tropical Storm Barry

| Tropical storm (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | July 9 – July 14 | ||

| Intensity | 55 mph (85 km/h) (1-min), 1005 mbar (hPa) | ||

Tropical Storm Barry developed out of a tropical wave which moved off the west coast of Africa on July 7. The wave quickly developed a low-level circulation by July 9 and was designated Tropical Depression Three. The depression was located midway between Africa and the Lesser Antilles and traveling to the northwest in response to an area of high pressure located north of the Azores. The depression was upgraded to Tropical Storm Barry on July 11. Barry slowly intensified and reached its peak intensity of 55 mph (85 km/h) the next day. By July 13, Barry weakened back to a depression and dissipated shortly after while located 545 mi (880 km) northeast of the Lesser Antilles.[23]

Hurricane Chantal

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | July 30 – August 3 | ||

| Intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min), 984 mbar (hPa) | ||

Hurricane Chantal originated from an Intertropical Convergence Zone disturbance first observed near Trinidad, but did not develop into Tropical Depression Four until north of the Yucatan Peninsula on July 31. The tropical depression quickly intensified into a tropical storm as it northward, receiving the name Chantal. Chantal further intensified into a Category 1 hurricane before landfall at High Island, Texas on August 1. After making landfall, Chantal initially rapidly weakened inland, deteriorating back to a tropical storm only five hours later. Chantal continued rapidly weaken inland, and was downgraded to a tropical depression early on August 2. The weak tropical depression tracked north-northwestward, and dissipated over Oklahoma on August 3. The remnants of Chantal crossed the Central and Eastern United States, before reaching Atlantic Canada. The remnants of Chantal were last noted over Canada, passing over Newfoundland on August 7 as Hurricane Dean approached.[24]

Similar to Tropical Storm Allison, there was heavy rainfall in Louisiana and Texas, although lesser amounts were recorded, peaking at 20 in (508 mm) in Friendswood, Texas.[25] There were 13 fatalities associated with Chantal, including a crew of 10 on the oil-rig construction vessel Avco 5, which capsized off Morgan City, Louisiana.[6] Damage caused by wind and flooding was estimated at $100 million (1989 USD, $177 million 2012 USD).[7]

Hurricane Dean

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | July 31 – August 9 | ||

| Intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min), 968 mbar (hPa) | ||

Hurricane Dean originated from a tropical wave that developed into Tropical Depression Five on July 31. The tropical depression was situated about half way between Cape Verde and the Lesser Antilles, and intensified into Tropical Storm Dean on August 1. Dean headed generally west-northwestward, and eventually intensified into a hurricane on the following day. Dean remained a weak Category 1 hurricane as it curved northward, bypassing the Lesser Antilles. Tracking northward, Dean accelerated and intensified into a Category 2 hurricane as it crossed Bermuda late on August 6. Continuing to accelerate, Dean curved northeastward, and weakened back to a tropical storm before making landfall in southern Newfoundland on August 8. Dean continued in the northeast direction and lost tropical characteristics south of Greenland on the following day.[26]

As Dean approached the Lesser Antilles, heavy rainfall and strong winds were reported in Antigua and Barbuda. Effects were similar on Bermuda, with winds gusting up to 113 mph (182 km/h) and 3-5 in (76.2–127 mm) of rainfall. Flooding was reported on Bermuda, and damage on the island was nearly $9 million (1989 USD, $15.9 million 2012 USD). Although Dean caused no fatalities, 16 people were injured in Bermuda.[8] In Atlantic Canada, light to moderate rainfall was reported, and tropical storm force winds were observed in some areas.[27] Furthermore, waves at 26 ft (7.92 m) were reported on Sable Island.[28]

Tropical Depression Six

| Tropical depression (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | August 16 – August 16 | ||

| Intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min), Unknown | ||

Tropical Depression Six had developed on August 16 from a tropical wave about 600 mi (965 km) east of the Leeward Islands. Because of its close proximity to the Lesser Antilles, a tropical storm watch was issued for that area of the Caribbean Sea. After less than 24 hours as a tropical depression, an upper-level low increased wind shear on the system, and it dissipated later that day.[16] The wave eventually split in two, with the south part eventually becoming Hurricane Lorena in the eastern Pacific Ocean.[29]

Hurricane Erin

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | August 18 – August 27 | ||

| Intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min), 968 mbar (hPa) | ||

An organized tropical wave was seen emerging off the coast of Africa on August 16 by METEOSAT satellite imagery. Once the system emerged off the coast of Africa into the cool eastern Atlantic Ocean, its convection diminished but left a small, well-organized low-level circulation. Slowly the tropical wave began to regain its convection and it became a tropical depression just southeast of the Cape Verde Islands early on August 18 based on Dvorak satellite observations. Erin became a tropical storm on August 19 while 500 mi (804.7 km) west of Cape Verde. The interaction between the tropical depression, a tropical wave moving through the central Atlantic, and a subtropical system to the north, caused Erin to move north-northwestward. It continued to be steered north-northwestward until August 21, when it turned northwards.[30]

Erin became a hurricane on August 22 after being in the environment of the northeastern quadrant of an upper-level low, which caused the stream above to become weaker and more conflicting. It slowed and began to move more northwestward while northeast of the upper-level low. However, shortly afterward, a wave moving westward into Erin forced it to move north and eventually north-northeast. The storm then began weakening and degenerated into a tropical storm on August 27. Shortly thereafter, Erin transitioned into an extratropical cyclone.[30]

Hurricane Felix

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | August 26 – September 9 | ||

| Intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min), 979 mbar (hPa) | ||

The eighth tropical depression of the season developed on August 26, from a tropical wave that emerged from Africa two days prior. Quickly intensifying, the tropical depression had become Tropical Storm Felix near Cape Verde. Felix headed northward thereafter, and then northwestward, weakening back to a tropical depression by August 29 from strong upper-level wind shear. Heading northwestward, Felix eventually curved to the north by September 1. While remaining near stationary as it headed northward, Felix re-intensified into a tropical storm. Felix then curved to the west-northwest, intensifying further as it did so. Finally, after 13 days, Felix intensified enough to be considered a hurricane.Upper level wind shear increased again on Felix, and it weakened back to a tropical storm on September 7. Felix gradually weakened thereafter, and meandered in the northern Atlantic until becoming extratropical far to the northwest of the Azores on September 9.[31]

Tropical Depression Nine

| Tropical depression (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | August 27 – August 28 | ||

| Intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min), Unknown | ||

Tropical Depression Nine developed from a tropical wave 490 mi (790 km) east of Barbados on August 27. However, on the following day, an Air Force plane did not indicate a low-level circulation, and Tropical Depression Nine had degenerated back into a tropical wave.[16] Tropical Depression Nine did not re-develop in the Atlantic or the Caribbean Sea, although the remnants entered the Pacific and regenerated into Hurricane Octave on September 8.[32]

Hurricane Gabrielle

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | August 30 – September 13 | ||

| Intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min), 935 mbar (hPa) | ||

The tenth tropical depression of the season developed from a tropical wave on August 30. The depression quickly intensified into Tropical Storm Gabrielle on the following day. Gabrielle moved generally westward, but curved slightly west-northwestward after intensifying into a hurricane on September 1. Further intensification continued, and Gabrielle eventually peaked as a moderately strong Category 4 hurricane on September 5. After becoming a Category 4 hurricane, Gabrielle slowly curved nearly due north.[33] Gabrielle significantly weakened while heading northward, and maximum sustained winds dropped from a low-end Category 4 hurricane intensity, to a strong Category 2 hurricane, within 12 hours on September 7. While weakening as it headed northward, Gabrielle bypassed the island of Bermuda early on September 8.[34] Gabrielle further weakened to a Category 1 hurricane late on September 8, and became nearly stationary roughly almost halfway between Bermuda and Cape Race, Newfoundland. Remaining nearly stationary, Gabrielle weakened to a tropical storm, and headed due westward on September 10. After heading westward, Gabrielle made a sharp turn to the northeast on September 11, and it weakened to a tropical depression on the following day. By September 13, the depression merged with a storm developing off Newfoundland.[34]

Although it never approached land, Gabrielle was an extremely large and powerful storm that generated swells up to 20 ft (6 m) all the way from the Lesser Antilles to Canada; waves reached a height of 30 ft (9 m) in Nova Scotia. Large waves responsible for eight deaths on the East Coast of the United States; almost all of the fatalities occurred in New England.[9] In addition, one fatality was reported in Canada, when a man drowned near Ketch Harbor, Nova Scotia.[10]

Hurricane Hugo

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | September 10 – September 23 | ||

| Intensity | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-min), 918 mbar (hPa) | ||

Hugo developed from a tropical wave near Cape Verde on September 10. Classified as Tropical Depression Eleven, it headed generally westward, and intensified into Tropical Storm Hugo on September 11. Further intensification was somewhat slow, and Hugo became a hurricane by September 13. After becoming a major hurricane early on September 15, rapid intensification commenced, and less than 24 hours later, Hugo peaked as a low-end Category 5 hurricane. Hugo was therefore, the most intense tropical cyclone of the 1989 Atlantic hurricane season. Six hours later, Hugo weakened back to a Category 4 hurricane. After weakening down to a low-end Category 4 hurricane on September 17, Hugo entered the Caribbean Sea after passing between Guadeloupe and Montserrat with winds near 140 mph (230 km/h) and later made landfall on St. Croix at the same intensity. After weakening to a Category 3, Hugo made landfall on eastern Puerto Rico, and re-emerged into the Atlantic on September 18. After re-emerging into the Atlantic, Hugo weakened further to a Category 2 hurricane. As Hugo accelerated to the northwest, re-intensification occurred, and it eventually reached a secondary peak intensity as a low-end Category 4 hurricane. Early on September 22, Hugo made landfall near Charleston, South Carolina with winds of 140 mph (225 km/h). After landfall, Hugo rapidly weakened as it turned to the northeast,[35] and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone in northwestern Pennsylvania on September 23. The remnants continued rapidly northeastward, and dissipated on September 25 near Greenland.[36]

Hugo posed a significant threat to much of the eastern Caribbean and to the East Coast of the United States, as a result, over 30 tropical storm/hurricane watches and warnings were issued in relation to the storm.[37][38] While crossing through the Caribbean, Hugo dropped heavy rainfall and caused very high winds resulting in the damage or destruction of houses and crops.[39] Hugo responsible for $3 billion (1989 USD, $5.31 billion 2012 USD) in damages and over 70 deaths. In the United States, the hurricane caused $7 billion (1989 USD, $12.4 billion 2012 USD) in damages and 35 deaths, mostly in South Carolina.[11][39] Hugo was the costliest tropical cyclone in American history and in the Atlantic basin at the time, however, it was later surpassed by Hurricane Andrew of 1992; it was further surpassed by Hurricanes Charley, Frances, Ivan, and Jeanne of 2004;[12] Hurricanes Katrina (which also surpassed Andrew),[40] Rita,[41] and Wilma in 2005;[42] and Hurricane Ike in the 2008 Atlantic hurricane season. As a result, Hugo is now the ninth costliest hurricane in the Atlantic basin (tied with Hurricane Jeanne).[43]

Tropical Storm Iris

| Tropical storm (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | September 16 – September 21 | ||

| Intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min), 1001 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave moved off the coast of northwest Africa on September 12, showing signs of organization three days later. Late on September 16, the National Hurricane Center classified it as Tropical Depression Twelve, about halfway between the southern Lesser Antilles and the Cape Verde islands. It slowly strengthened despite its proximity to Hurricane Hugo, and intensified into Tropical Storm Iris early on September 18. After attaining that status, Iris turned to the north-northwest, paralleling the Leeward Islands,[44] and initially there was uncertainty in its path due to potential Fujiwhara, or binary interaction with Hugo.[45] On September 19, Iris attained peak winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) about 260 mi (420 km) northeast of Barbuda.[44] After reaching peak intensity, Iris weakened due to increased wind shear from Hugo. On September 21, the winds decreased below tropical storm status, after the center became exposed from the convection. The next day Iris dissipated,[44] although a remnant circulation persisted and tracked toward southern Florida.[46]

As Iris approached the Lesser Antilles, a tropical storm warning was issued for Barbados and St. Vincent and the Grenadines on September 18. Simultaneously, a tropical storm watch was issued for Trinidad and Tobago. Six hours later, both the tropical storm watch and warning was discontinued. While Iris was a strong tropical storm, it produced 7.53 in (191 mm) of rainfall on Saint John in the U.S. Virgin Islands, resulting in flooding. There were few reports of winds or rainfall on other islands, due to Hugo destroying observation stations a few days prior.[45]

Tropical Depression Thirteen

| Tropical depression (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | October 2 – October 3 | ||

| Intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min), Unknown | ||

Tropical Depression Thirteen developed on October 2 from a tropical wave a few hundred miles east of the Lesser Antilles.[16] The National Hurricane Center monitored the tropical depression and issued marine advisories, although they were accidentally included in the database for the 1989 season in the east Pacific basin. Tropical Depression Thirteen was predicted to intensify into near hurricane status by October 5,[47] although a mid-latitude trough increased wind shear, inducing weakening.[16] As a result, forecasts for strengthening were lowered, although intensification into a tropical storm was still expected.[48][49] However, later on October 3, the National Hurricane Center instead began to forecast weakening on the depression.[50] Shortly before 0000 UTC on October 4, it was noted that satellite imagery only indicated a swirl of low-level clouds, and the depression was then declared dissipated.[16][51]

Hurricane Jerry

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | October 12 – October 16 | ||

| Intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min), 983 mbar (hPa) | ||

Hurricane Jerry formed from an African tropical wave that failed to developed until crossing the Yucatán Peninsula and emerging into the Bay of Campeche on October 12. Developed as the fourteenth tropical depression of the season, the system quickly intensified into Tropical Storm Jerry on the following day. It tracked generally northwards while intensifying, and reached hurricane strength on October 15.[52] After intensifying slightly more, Jerry made landfall near Jamaica Beach, Texas with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h). Jerry rapidly weakened after moving inland, and dissipated by October 16. The remnants moved through the Tennessee Valley ahead of a frontal zone, and eventually offshore the coast of the Mid-Atlantic states.[53]

As Jerry approached the coast, light storm surge occurred in Louisiana and Texas, with the highest waves reaching 7 ft (2.1 m) in Baytown, Texas. Three people died when an automobile was blown off the Galveston, Texas seawall and State Highway 87 was washed away from High Island, Texas to the eastern portion of Sea Rim State Park. This was the last time that Highway 87 was open to traffic across much of Jefferson County due to increasing erosion.[53][54] In addition, light to moderate rainfall fell in the path of Jerry and its remnants, with precipitation peaking at 6.40 in (163 mm) in Silsbee, Texas, and 6.71 in (170 mm) in eastern Kentucky.[55] Damage is estimated at $70 million (1989 USD, $124 million 2012 USD).[54]

Tropical Storm Karen

| Tropical storm (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | November 28 – December 4 | ||

| Intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min), 1000 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on November 13, and failed to organize until reaching the western Caribbean Sea. An upper-level anticyclone provided favorable conditions, allowing thunderstorms to concentrate around a developing low-level circulation. On November 28, satellite imagery and reconnaissance aircraft indicated the development of Tropical Depression Fifteen just north of the Honduras coast. It moved northwestward then northeastward, intensifying into Tropical Storm Karen on November 30 while southwest of Isla de la Juventud off the south coast of Cuba; it was named on the last day of the hurricane season. Within 12 hours of reaching tropical storm intensity, Karen reached peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h), and around the same time a building ridge in the Gulf of Mexico forced it southeastward.[56]

While Karen was still a tropical depression, tropical storm watches were issued for Cozumel on the Yucatan Peninsula, Isle de la Juventud, and western Cuba; the latter two were upgraded to warnings after Karen attained tropical storm intensity.[57] The storm dropped heavy rainfall in Cuba, reaching over 15 in (380 mm) on Isle de la Juventud. Wind gusts reached 60 mph (97 km/h), and there were reports of a tornado, but no damage or fatalities were reported. After affecting Cuba, Karen turned to the southwest while steadily weakening.[56] It briefly threatened Belize, prompting a tropical storm watch,[57] but the storm turned to the southeast and dissipated on December 4; its remnants later moved over Nicaragua.[56] Karen was the last tropical cyclone to exist in December until Hurricane Nicole in 1998.[58]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms that formed in the north Atlantic in 1989. The names not retired from this list were used again in the 1995 season. This is the same list used for the 1983 season except for Allison, which replaced Alicia.[1] Storms were named Allison, Erin, Felix, Gabrielle, Hugo, Iris, Jerry, and Karen for the first time in 1989. Names that were not assigned are marked in gray.

|

Retirement

The World Meteorological Organization retired one name in the spring of 1990: Hugo. It was replaced in the 1995 season by Humberto.[59]

Season effects

This is a table of the storms in 1989 and their landfall(s), if any. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but are still storm-related. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical or a wave or low.

| Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max wind (mph) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Landfall(s) | Damage (millions USD) |

Deaths | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Where | When | Wind

(mph) |

||||||||

| One | June 15 – June 16 | Tropical depression | 35 | Unknown | none | 0 | 0 | |||

| Allison | June 24 – July 1 | Tropical storm | 50 | 999 | Freeport, Texas | June 27 | 50 | 560 | 11 | |

| Barry | July 9 – July 14 | Tropical storm | 55 | 1005 | none | 0 | 0 | |||

| Chantal | July 30 – August 4 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 | 986 | High Island, Texas | July 31 | 80 | 100 | 13 | |

| Dean | July 31 – August 9 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 | 968 | Bermuda | August 6 | 100 | 9 | 0 | |

| Marystown, Newfoundland and Labrador | August 8 | 65 | ||||||||

| Six | August 16 – August 16 | Tropical depression | 35 | Unknown | none | 0 | 0 | |||

| Erin | August 18 – August 27 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 | 968 | none | 0 | 0 | |||

| Felix | August 26 – September 10 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 | 979 | Cape Verde Islands (Direct hit, no landfall) | September 25 | 45 | Minimal | 0 | |

| Nine | August 28 – August 30 | Tropical depression | 35 | Unknown | none | 0 | 0 | |||

| Gabrielle | August 30 – September 13 | Category 4 hurricane | 145 | 939 | none | 0 | 9 | |||

| Hugo | September 9 – September 25 | Category 5 hurricane | 160 | 918 | Guadeloupe | September 17 | 140 | 10,000 | 111 | |

| Vieques, Puerto Rico | September 18 | 125 | ||||||||

| Fajardo, Puerto Rico | September 18 | 125 | ||||||||

| Near Charleston, South Carolina | September 22 | 140 | ||||||||

| Iris | September 16 – September 21 | Tropical storm | 70 | 1001 | none | 0 | 0 | |||

| Thirteen | October 2 – October 3 | Tropical depression | 35 | Unknown | none | 0 | 0 | |||

| Jerry | October 12 – October 16 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 | 983 | Galveston, Texas | October 16 | 75 | 70 | 3 | |

| Karen | November 28 – December 4 | Tropical storm | 60 | 1000 | none | Minimal | 0 | |||

| Season Aggregates | ||||||||||

| 15 cyclones | June 24 – December 4 | 160 | 918 | 7 landfalls | 10,739 | 147 | ||||

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Atlantic hurricane seasons

- 1989 Pacific hurricane season

- 1989 Pacific typhoon season

- 1989 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- Southern Hemisphere tropical cyclone seasons: 1988–89, 1989–90

References

- ^ a b c d e Associated Press (June 1, 1989). "4 hurricane for the Atlantic predicted in 1989". Star-News. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=Lb8sAAAAIBAJ&sjid=lxQEAAAAIBAJ&pg=4610,13531&dq=1989+atlantic+hurricane+season&hl=en. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Dorst, Neil (January 12, 2010). "FAQ: When is hurricane season?". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/tcfaq/G1.html. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- ^ a b National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (May 27, 2010). "Background information: the North Atlantic Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/outlooks/background_information.shtml. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Case, Bob & Mayfield, Max (May 1990). "Atlantic hurricane season of 1989". National Hurricane Center. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/hurdat/mwr_pdf/1989.pdf. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ a b Case, Robert (August 16, 1989). "Tropical Storm Allison Preliminary Report, Page Four". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/allison/prelim04.gif. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Gerrish, Harold (November 22, 1989). "Hurricane Chantal Preliminary Report, Page Four". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/chantal/prelim04.gif. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Gerrish, Harold (November 22, 1989). "Hurricane Chantal Preliminary Report, Page Three". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/chantal/prelim03.gif. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Mayfield, Max (October 22, 1989). "Hurricane Dean Preliminary Report, Page Two". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/dean/prelim02.gif. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Case, Robert (November 23, 1989). "Hurricane Gabrielle Preliminary Report, Page Three". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/gabrielle/prelim03.gif. Retrieved November 17, 2010.

- ^ a b "1989-Gabrielle". Environment Canada. September 14, 2010. http://www.ec.gc.ca/Hurricane/default.asp?lang=En&n=ED9885C6-1. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ a b Grammatico, Michael (April 2006). "Hurricane Hugo - September 22, 1989". Archived from the original on 2009-10-26. http://www.webcitation.org/query?url=http://www.geocities.com/hurricanene/hurricanehugo.htm&date=2009-10-26+00:17:19. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ a b Landsea, Christopher (2004). "Costliest U.S. Hurricanes 1900-2004 (unadjusted)". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pastcost.shtml. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ a b c Dorst, Neal (January 21, 2010). "Subject: G1) When is hurricane season?". Hurricane Research Division. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/tcfaq/G1.html. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Hurricane Research Division (March 2011). "Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/hurdat/Comparison_of_Original_and_Revised_HURDAT_mar11.html. Retrieved 2011-08-03.

- ^ David Levinson (2008-08-20). "2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones". National Climatic Data Center. http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/research/2005/2005-atlantic-trop-cyclones.html. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g Avila, Lixion (May 1990). "Atlantic Tropical Systems of 1989". National Hurricane Center. http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/pdf/10.1175/1520-0493(1990)118%3C1178%3AATSO%3E2.0.CO%3B2. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- ^ Associated Press (June 16, 1989). "Pennsylvania tornado injures 7". Daily Union. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=hKpEAAAAIBAJ&sjid=J7YMAAAAIBAJ&dq=tropical%20depression&pg=1431%2C6388864. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- ^ "First tropical depression forms". The Hour. June 16, 1989. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=ESFJAAAAIBAJ&sjid=gAYNAAAAIBAJ&pg=1215,2485342&dq=tropical+depression+one&hl=en. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- ^ Case, Robert (August 16, 1989). "Tropical Storm Allison Preliminary Report, Page One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/allison/prelim01.gif. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Case, Robert (August 16, 1989). "Tropical Storm Allison Preliminary Report, Page Two". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/allison/prelim02.gif. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Roth, David (May 1, 2007). "Tropical Storm Allison - June 24-July 7, 1989". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. http://www.hpc.ncep.noaa.gov/tropical/rain//allison1989.html. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Roth, David (January 26, 2011). "Maximum Rainfall caused by Tropical Cyclones and their remnants per state (1950-2010)". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. http://www.hpc.ncep.noaa.gov/tropical/rain/tcstatemaxima.gif. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles (August 28, 1989). "Tropical Storm Barry Preliminary Report, Page One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/barry/prelim01.gif. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Gerrish, Harold (November 22, 1989). "Hurricane Chantal Preliminary Report, Page One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/chantal/prelim01.gif. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Roth, David (May 1, 2007). "Hurricane Chantal - July 31-August 4, 1989". National Hurricane Center. http://www.hpc.ncep.noaa.gov/tropical/rain/chantal1989.html. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Mayfield, Max (October 22, 1989). "Hurricane Dean Preliminary Report, Page One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/dean/prelim01.gif. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ "1989-Dean". Environment Canada. September 14, 2010. http://www.ec.gc.ca/Hurricane/default.asp?lang=En&n=BA1F7004-1. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ Associated Press (1989). "Hurricane sweeps past Nova Scotia". Syracuse Herald Journal.

- ^ Gerrish, Harold (1989). "Hurricane Lorena Preliminary Report, Page One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/epacific/ep1989-prelim/lorena/prelim01.gif. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Gross, Jim (December 4, 1989). "Hurricane Erin Preliminary, Page One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/erin/prelim01.gif. Retrieved November 2, 2010.

- ^ Clark, Gilbert (November 17, 1989). "Hurricane Felix Preliminary Report, Page One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/felix/prelim01.gif. Retrieved November 2, 2010.

- ^ Clark, Gilbert (November 9, 1989). "Hurricane Octave Preliminary Report". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/epacific/ep1989/octave/prenhc/prelim01.gif. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ Case, Robert (November 23, 1989). "Hurricane Gabrielle Preliminary Report, Page One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/gabrielle/prelim01.gif. Retrieved November 17, 2010.

- ^ a b Case, Robert (November 23, 1989). "Hurricane Gabrielle Preliminary Report, Page Two". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/gabrielle/prelim02.gif. Retrieved November 17, 2010.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles (November 15, 1989). "Hurricane Hugo Preliminary Report, Page One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/hugo/prelim01.gif. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles (November 15, 1989). "Hurricane Hugo Preliminary Report, Page Two". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/hugo/prelim02.gif. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles (November 15, 1989). "Hurricane Hugo Preliminary Report, Page Ten". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/hugo/prelim10.gif. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles (November 15, 1989). "Hurricane Hugo Preliminary Report, Page Eleven". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/hugo/prelim11.gif. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ a b Lawrence, Miles (November 15, 1989). "Hurricane Hugo Preliminary Report, Page Three". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/hugo/prelim03.gif. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ Knabb, Richard; Rhome, Jamie; Brown, Daniel (August 10, 2006). "Hurricane Katrina Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-AL122005_Katrina.pdf. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ Knabb, Richard; Rhome, Jamie; Brown, Daniel (August 14, 2006). "Hurricane Rita Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-AL182005_Rita.pdf. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ Pasch, Richard; Blake, Eric; Cobb III, Hugh; Roberts, David (September 28, 2006). "Hurricane Wilma Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-AL252005_Wilma.pdf. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ Berg, Robbie (May 3, 2010). "Hurricane Ike Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-AL092008_Ike_3May10.pdf. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ a b c Gerrish, Harold (November 20, 1989). "Tropical Storm Iris Preliminary Report, Page One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/iris/prelim01.gif. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ a b Gerrish, Harold (November 20, 1989). "Tropical Storm Iris Preliminary Report, Page Two". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/iris/prelim02.gif. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ Gerrish, Harold (November 20, 1989). "Tropical Storm Iris Preliminary Report, Page Three". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/iris/prelim03.gif. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ "Tropical Depression Thirteen Marine Advisory Number One". National Hurricane Center. October 2, 1989. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/epacific/ep1989/td13e/marine/tcm0222z.gif. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ "Tropical Depression Thirteen Marine Advisory Number Two". National Hurricane Center. October 3, 1989. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/epacific/ep1989/td13e/marine/tcm0304z.gif. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ "Tropical Depression Thirteen Marine Advisory Number Three". National Hurricane Center. October 3, 1989. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/epacific/ep1989/td13e/marine/tcm0310z.gif. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ "Tropical Depression Thirteen Marine Advisory Number Four". National Hurricane Center. October 3, 1989. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/epacific/ep1989/td13e/marine/tcm0316z.gif. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ "Tropical Depression Thirteen Marine Advisory Number Five". National Hurricane Center. October 3, 1989. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/epacific/ep1989/td13e/marine/tcm0321z.gif. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ Mayfield, Max (November 21, 1989). "Hurricane Jerry Preliminary Report, Page One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/jerry/prelim01.gif. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Mayfield, Max (November 21, 1989). "Hurricane Jerry Preliminary Report, Page Two". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/jerry/prelim02.gif. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Mayfield, Max (November 21, 1989). "Hurricane Jerry Preliminary Report, Page Three". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/jerry/prelim03.gif. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- ^ Roth, David (June 16, 2007). "Hurricane Jerry - October 12–18, 1989". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. http://www.hpc.ncep.noaa.gov/tropical/rain/jerry1989.html. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c Avila, Lixion (December 22, 1989). "Tropical Storm Karen Preliminary Report, Page One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/karen/prelim01.gif. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Avila, Lixion (December 22, 1989). "Tropical Storm Karen Preliminary Report, Page Five". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1989-prelim/karen/prelim05.gif. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ Hurricane Research Division (August 2011). "Atlantic hurricane best track (Hurdat)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/hurdat/tracks1851to2010_atl_reanal.html. Retrieved 2011-09-19.

- ^ National Hurricane Center (March 16, 2011). "Retired Hurricane Names Since 1954". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/retirednames.shtml. Retrieved July 14, 2011.

External links

- Monthly Weather Review

- Detailed information on all storms from 1989

- U.S. Rainfall caused by 1989 tropical cyclones

- UNISYS hurricane tracks for 1989

|

Tropical cyclones of the 1989 Atlantic hurricane season |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Book · Category · Portal · WikiProject · Commons |

|

|

|||||